Purple Cambridge: A Chronicling of Presidential Elections, 1848–1924

How was the most electorally lopsided place in New England once a tossup?

This piece was originally published on Medium in December 2021; I’m reposting it on Substack for convenience.

This article presents ward-level maps and analysis of presidential elections from 1848 to 1924 in the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts. It first provides background on Cambridge, detailing the distinct neighborhoods that influenced its early voting patterns. Next, it examines the elections individually, placing the results in local context. Afterward, a gallery of charts illustrating long-term trends is included. The epilogue discusses why Cambridge became uncompetitive in presidential elections after 1924 and remains so today.

Introduction

Founded in 1630 by Puritan settlers, Cambridge was originally intended to be the capital of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Cambridge Historical Commission, n.d.). The original settlement consisted of a small grid near a sharp bend in the Charles River. The village that formed was a quiet agricultural community anchored by Harvard College, which was created in 1636 to educate future clergymen. Until after the American Revolution, Cambridge maintained a rural character due to its relative isolation from Boston; no direct route to the city existed, so traveling there required a circuitous eight-mile trek.

Outside of the settlement, Cambridge was entirely undeveloped, consisting merely of pastures and marshland (Freeman, 2000, p. 18). Francis Dana, a renowned lawyer who served on Massachusetts’ Supreme Court, was instrumental in attracting development beyond the original village. He began purchasing farmland outside the village in the 1780s, building himself a mansion in an area that became known as Dana Hill (21). His continued acquisitions, along with large inheritances, soon made him the principal landowner east of Harvard. Along with other investors, he spearheaded the construction of the West Boston Bridge in 1793, linking Cambridge and Boston for the first time (22). The bridge drastically shortened travelers’ journeys, prompting the creation of new roads to the village (29). A new neighborhood, Cambridgeport, sprouted along the newly built thoroughfares; by 1806, its population was estimated at 1,000 residents (Cambridge Historical Commission, 1971, p. 18).

Dana’s investments proved hugely successful in spurring growth. Andrew Craigie, a former revolutionary and prominent land speculator, had similar ideas. Craigie clandestinely bought up virtually the entire area known as Lechmere’s Point, located at the extreme northeastern edge of Cambridge (Maycock, 1989, p. 17). In 1805, he submitted a petition to build his own bridge to Boston (19). His proposal received significant blowback from the operators of the West Boston Bridge; he became notorious for his persistence in convincing the legislature to approve his plans (20–21). After several years of contentious debate, the Canal Bridge was finally opened in 1809 (22). The surrounding area, laid out in an organized street grid, came to be known as East Cambridge. Over the next few decades, it became a thriving center for industry, particularly glassmaking; seven such companies were established in the neighborhood between 1814 and 1849 (174).

Amid this frenzy of activity, the original village received the nickname of “Old Cambridge.” Cambridgeport and East Cambridge were thriving regions with constant construction and lively business scenes (Rodley, 2017). By contrast, inward-looking Old Cambridge was stodgy and quiet, increasingly reliant on Harvard for relevance. In a symbolic defeat for the original village, Craigie persuaded Middlesex County to move its courthouse from Old Cambridge to East Cambridge, even putting up the money for the new building himself (Rodley, 2017). Relations between the three communities turned increasingly acrimonious. Old Cambridge residents were dismayed at their loss of status; those outside it were frustrated with the village’s stubborn elitism. These tensions culminated when Old Cambridge residents attempted to secede on multiple occasions between 1842 and 1844 (Rodley, 2017). Their proposal insisted on Old Cambridge keeping the “Cambridge” name and laid claim to two-thirds of Cambridge’s land area. It failed to achieve meaningful support outside the village; in 1846 the town meeting voted to incorporate as a city, uniting the rival communities once and for all.

The new city was divided into three wards, broadly respecting the three communities: Ward 1 comprised Old Cambridge along with outlying areas to the north and west, Ward 2 included all of Cambridgeport, and Ward 3 was coterminous with East Cambridge. Cambridgeport attracted small-scale businesses like inns and taverns; its population was largely composed of middle-class tradespeople (Cambridge Historical Commission, 1971, p. 25). East Cambridge, meanwhile, attracted waves of immigrants — particularly refugees from Ireland’s potato famine — who found employment in its booming factories; by 1850, 22% of the neighborhood’s population was Irish-born (Maycock, 1989, p. 221).

Sourcing & Acknowledgments

During the time period this piece covers, three major newspapers existed in Cambridge. The Cambridge Chronicle was founded in 1848 and typically favored Republican candidates. The Cambridge Tribune, which printed its first issue in 1876, also had a Republican bent. The Cambridge Sentinel began publishing in 1903 and always enthusiastically backed Democratic candidates. To view individual issues of these papers, navigate to the Cambridge Public Library’s digital archives. All of the ward-level election results mapped here were obtained from the Chronicle archives. Needless to say, I am deeply grateful to the Library for their work making these resources accessible.

I am also grateful to the Internet Archive’s Open Library, which enabled me to access many of the books I cite. Finally, I am grateful to the Boston Public Library; their Digital Commonwealth collection hosts the atlases I used to create the shapefiles for these maps.

The Elections

1848

Leading up to the 1848 election, Massachusetts Whigs were far from united. The state had been a Whig stronghold for the last two decades, but an internecine rift was opening up over the issue that would eventually upend the party — slavery. For one faction of the party, the Cotton Whigs, “slavery was not so important as certain commercial problems” (Luthin, 1941, p. 622). This bloc prioritized maintaining good relations with the South since Massachusetts’ burgeoning industries profited from buyers there. Conscience Whigs, on the other hand, were vehemently anti-slavery; for them, everything paled in importance to stopping its spread.

The party’s nomination of Zachary Taylor, a Southern slaveholder, prompted many Conscience Whigs to abandon the party label. They lined up behind former President Martin Van Buren, who ran under the Free Soil Party, a single-issue party dedicated to opposing slavery (623). Concerned with Taylor’s prospects, Whig congressman Abraham Lincoln traveled to Massachusetts to rally support for him; he spoke in Cambridge on September 20 (629).

The wealthy academics of Old Cambridge were staunchly loyal Whigs; indeed, Harvard “furnished many of the ideas of the Whig party” (620). Although Van Buren ran strongly in Massachusetts, even finishing ahead of Democrat Lewis Cass, Cambridge stuck comfortably with the party it so strongly identified with. Thus, Taylor became the first person to win the newly incorporated city. Appropriately, he was strongest in Ward 1, where he took 67% of the vote. 173 years later, Cass’ showing remains the worst for a Democrat in the city’s history.

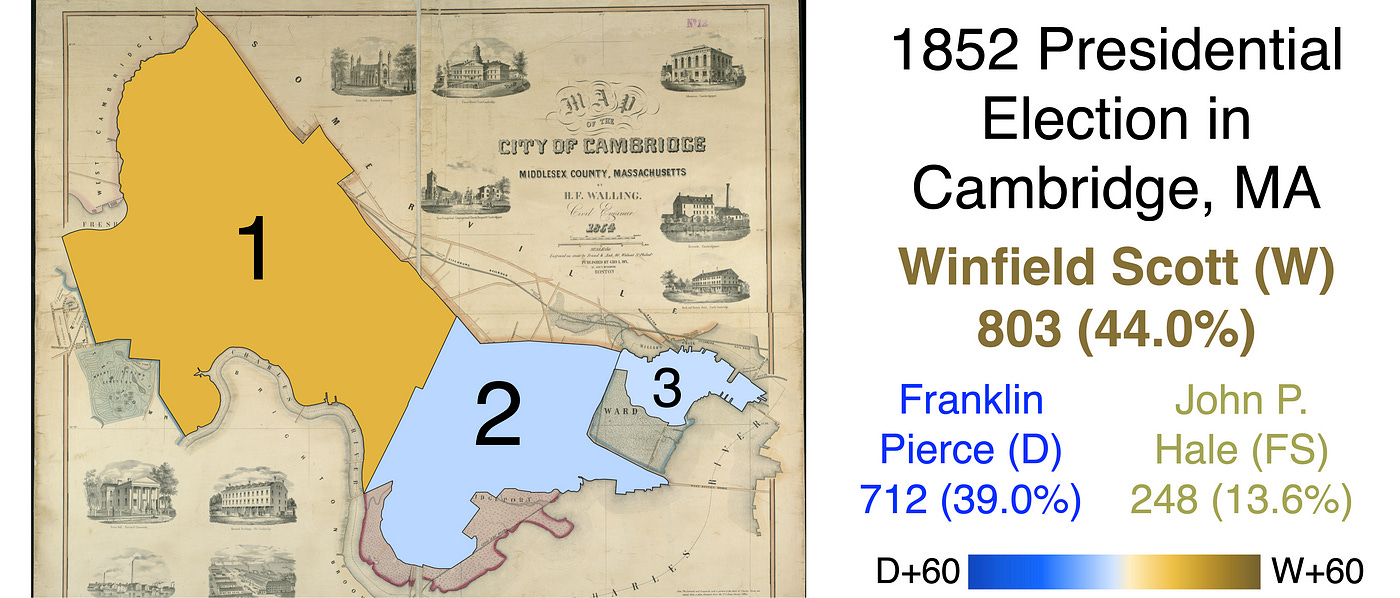

1852

By 1852, the Whigs were severely fractured along geographic lines and rapidly declining in relevance. Millard Fillmore, who took over as President when Taylor died in office, deeply alienated northern Whigs by enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act. Heading into the 1852 convention, Boston’s Whigs mostly supported Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who had previously served for 19 years as a Senator from Massachusetts (Rich, 1971). However, Webster lost the nomination to Winfield Scott, a Virginian general who emerged as the consensus choice among Northerners who wanted to stop Fillmore. After the convention, disaffected Boston Whigs congregated at Faneuil Hall. The auditorium there was “packed with Websterians, who, at a ‘rejection meeting’, formally protested against Scott’s candidacy” (Fuess, 1930, p. 345).

Scott suffered a lopsided defeat nationwide; Massachusetts was one of just four states he won. He lost the city of Boston, a first for any Whig presidential or gubernatorial candidate since 1836 (Rich, 1971, p. 265). In Cambridge, though, he managed to hold on. He took 55% of the vote in Ward 1, where Democrat Franklin Pierce was held to 28%. Pierce carried the other two wards, though he did so with narrow pluralities. Even though Cambridge’s population was swelling rapidly at the time, fewer votes were cast in 1852 than in 1848. This dip in turnout likely reflected voters’ distaste for both Scott and the Democratic Party.

This would be the last election until 1876 where Boston and Cambridge voted for different parties.

1856

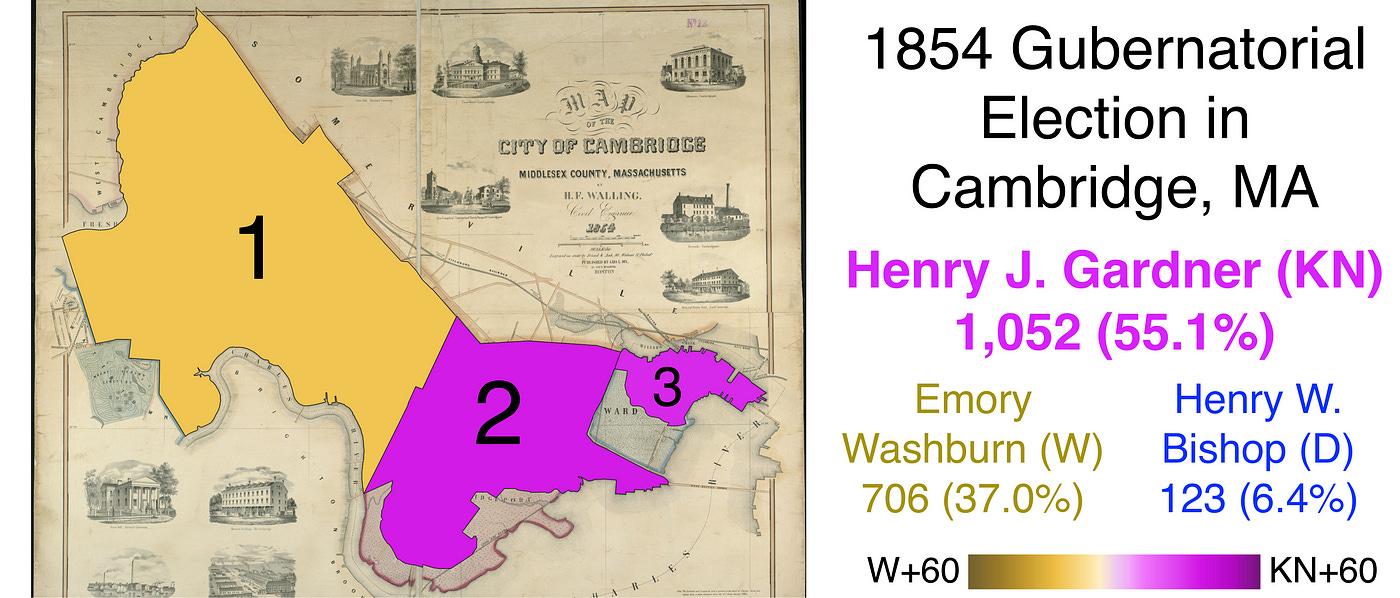

In 1854, a political wave swept Massachusetts. Boston had absorbed a massive influx of Irish refugees fleeing the potato famine, stoking anti-immigrant sentiment; the Know-Nothing Party, a nativist political movement, took advantage of the vacuum created by the Whigs’ collapse. The movement was far more successful in Massachusetts than anywhere else (Kierdorf, 2016).

Out of nowhere, Know-Nothings won total control of state government in the 1854 midterms. They flipped the entire State Senate, gained all 11 Congressional seats, and claimed the governorship in a drubbing. They used their newfound power to mandate the teaching of the Protestant Bible in schools, ban Catholics from holding public office, and fire Irish state workers (Kierdorf, 2016). Their agenda also incorporated planks of populism; they forbade Massachusetts from enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act and fiercely regulated banks and insurance companies, “[addressing] many of the social problems that had been ignored by the other parties” (Kierdorf, 2016). Many anti-slavery reformers strategically backed the Know-Nothings, calculating that generating panic over the Irish was the most effective way to recruit the new supporters they needed to win office (Handlin, 1941, p. 200).

Though no locale entirely avoided the tidal wave, members of the business-friendly, traditionally Whiggish aristocratic elite were most resistant to the reactionary Know-Nothings. In cities across Massachusetts, Know-Nothing candidates performed far worse in high-income wards than low-income wards (Mulkern, 1990, p. 86). Henry Gardner, the winning gubernatorial candidate, carried Cambridge with 55% of the vote — a massive achievement for a non-Whig — yet still lost Old Cambridge, getting just 34% in Ward 1.

By 1856, however, the Know-Nothings’ momentum had dissipated. The presidential campaign was dominated by the issue of slavery; the upstart Republican Party, formed in opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, simultaneously attracted anti-slavery voters and former Know-Nothings. Indeed, across the Northern states, most Know-Nothings “had already abandoned that party for the Republicans” (Foner, 1970, p. 250). Republican nominee John C. Frémont, who won Massachusetts in a romp, carried Cambridge by a smaller but still very comfortable margin. Former President Millard Fillmore, running as a Know-Nothing, outran his statewide showing by 7 points. In Ward 1, he even finished ahead of Democrat James Buchanan, who garnered just 21% of the vote there.

1860

In 1857, Cambridge created two new wards due to explosive population growth. This was not accomplished without controversy: in September 1857, the Chronicle reported that “a little feeling is already manifested by some of our citizens in relation to the proposed lines” (Sep. 19, 1857). Residents of Old Cambridge initially contended that their home Ward 1 was not populous enough to be split. Then, living up to their self-aggrandizing reputation, they insisted on retaining their designation as Ward 1. The Chronicle mocked them (“they are too sensitive altogether, and we should not be surprised if some among them should yet assert that Old Cambridge was the Garden of Eden”), but they got their way.

Ward 5 was split off from Ward 1 and covered North Cambridge. Anchored by North Avenue, a nascent thoroughfare with a post office and railroad station, this area maintained an idyllic, rural character even as the rest of Cambridge suburbanized. In 1859, the Chronicle wrote that “North Avenue … to those who are not averse to a little greater distance from the metropolis, offers very desirable locations for dwellings” (Oct. 22). Ward 5 was by far the least populous ward; in 1860, it would cast just 8% of the city’s vote. Although East Cambridge remained the primary haven for Irish immigrants, North Cambridge also fostered a sizeable community. One neighborhood in the area even became known as “Dublin” (Sullivan, 2015).

Edward Everett was a prominent pastor and Harvard professor who served as Governor of Massachusetts from 1836 to 1839. A blue-blooded Whig, he was left politically homeless when his party collapsed. He desired “a new national conservative party” with the express intention of promoting national unity (Brown, 1983, p. 70). The new Constitutional Union Party, formed to contest the 1860 election, was precisely what Everett was looking for; subsequently, he became deeply invested in its success (71). At the party’s convention, he accepted the vice presidential nomination.

Everett’s strong local ties appeared to make a difference, particularly in Old Cambridge. The Constitutional Union ticket took 13% of the statewide vote but reached nearly 32% in Ward 1. Additionally, Massachusetts Catholics voted against Republican Abraham Lincoln by almost three-to-one; while Douglas won many of them, some went to the Constitutional Unionists (Baum, 1984, p. 94). Lincoln still won a comfortable victory, as pro-slavery Democrat Stephen Douglas had little appeal in Cambridge. He took just 12% of the vote in Ward 1; no Democrat would ever capture that small a vote share in a ward containing Old Cambridge again. Mirroring Buchanan’s performance in 1856, Douglas finished in third place in Wards 1, 2, and 4. This election marked the last time a Democrat would come third in any of Cambridge’s wards.

1864

During the Civil War, Massachusetts was an ardently pro-Union state. Chapters of the abolitionist Loyal National League were strong there (Newman, 1944, p. 308). Popular Republican governor John Albion Andrew, who won Cambridge by 32 points in his 1863 re-election, was part of a group of governors known as the Great War Governors — staunch defenders of Lincoln who advocated for the emancipation of slaves (Engle, 2017, p. 43).

Yet for much of 1864, Lincoln took flak from the Radical Republicans, a faction of his party that believed he was not being harsh enough on the Confederacy (Cunningham, 2021). The disgruntled radicals held a “Radical Democracy” convention and chose John C. Frémont as their nominee (Newman, 1944, p. 315). Over the summer, there was real doubt as to whether Lincoln could win re-election; the Union Army’s capture of Atlanta in September was decisive in shifting momentum his way (Cunningham, 2021). Cambridge citizens enthusiastically celebrated the victory: “a display of fireworks was made on Main street … and at an early hour the City Hall was crowded” (Cambridge Chronicle, Sep. 10, 1864). Eventually, Frémont was persuaded to drop out of the race and unite behind Lincoln.

In Cambridge, Lincoln enjoyed a much more decisive victory than he did in 1860. His vote share increased by double digits in every ward, and he became the first presidential candidate to earn over 60% of the city’s vote. In turn, local Republican candidates outperformed expectations this cycle. In one race, “the Union men who were engaged in canvassing in Cambridge… ventured to pledge Cambridge for a majority for [Republican Samuel] Hooper of 500 votes. The result showed a majority of more than 1200” (Chronicle, Nov. 12, 1864).

As well as Lincoln did in Cambridge, he did even better statewide. His 72–28 victory remains the best Republican showing in Massachusetts’ history. Besides the presence of Democratic-leaning Irish voters, one potential reason Lincoln fared slightly worse in Cambridge is the city’s strong Unitarian contingent. Unitarians “controlled Harvard College and sustained numerous learned societies, charitable organizations, publishing houses, and magazines” (Baum, 1984, p. 98). Ideologically, they prioritized maintaining social order and the status quo, distrusting the abolitionist zeal of the Radical Republicans. The wartime cause prompted some Unitarians to back Lincoln, such as Edward Everett, who even volunteered to be an elector for him. Still, statistical estimates indicate McClellan did slightly better among Unitarian voters than he did statewide (99).

1868

The 1868 election was fought largely over the nature of Reconstruction. After President Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson took office. He quickly dismayed the Radical Republicans by vetoing bills that would give freedmen civil rights and expressing a desire to pardon Confederate leaders (Senate Historical Office, n.d.). The Republican convention reacted by unanimously nominating popular war hero Ulysses S. Grant, who sympathized with the Radicals.

With the war fresh in voters’ memories, Massachusetts Republicans attacked Democratic nominee Horatio Seymour, a Southern sympathizer who opposed the Republicans’ Reconstruction program. Springfield Republican editor Samuel Bowles compared him to Clement Vallandigham, a pro-slavery Democrat who opposed the war (Baum, 1984, p. 140). Lending credence to the attacks was Seymour’s running mate, Francis Blair, who “engaged in demagoguery that made the party’s campaign one of the most racist in American history” (Sacco, 2017). The Chronicle issued a strong endorsement of Grant, declaring that “the great question is, whether freedom and equality … shall be forever established, or, whether we shall ignobly submit to the domination and control of Southern rebels and Northern copperheads” (Oct. 31, 1868).

Grant won Cambridge by 22 points, down from Lincoln’s 31-point victory. The Chronicle noted that many naturalized citizens attended a meeting of Cambridge Democrats called to ratify Seymour’s nomination. “For some reason or other,” it noted, “[naturalized citizens] seem to have a peculiar affinity for every thing that goes by the name of Democracy” (Aug. 1, 1868). Indeed, Seymour did 13 points better than McClellan in heavily Irish Ward 3, which marked his biggest improvement in any ward. The Republican ticket still dominated in Old Cambridge; Ward 1 barely budged from 72–28 Lincoln to 71–29 Grant.

1872

In 1872, a faction of Republicans dissatisfied with Grant’s administration splintered off and formed the Liberal Republican Party. At the Liberal Republicans’ convention, the New England delegates supported Bay State native Charles Francis Adams. Adams was initially favored to claim the nomination, but he lost on the sixth ballot to newspaper mogul Horace Greeley. In turn, “the Adams men from New England were appalled, and many of them supported Grant in preference to Greeley” (McPherson, 1965, p. 51). Democrats, convinced that uniting with the Liberal Republicans represented their only chance at toppling Grant, backed Greeley and elected not to run a candidate of their own.

Greeley’s nomination greatly pleased Massachusetts Republicans, who realized that he was highly unlikely to topple Grant and “presented far less of a threat in their districts than an Adams candidacy” (Baum, 1984, p. 166). In contrast to Grant’s hardline approach of enforcing Reconstruction with a military presence, Greeley advocated a more conciliatory tack. In his acceptance letter, he asserted that “the masses of our countrymen, North and South, are eager to clasp hands across the bloody chasm which has too long divided them” (Chronicle, May 25, 1872). This cordial outreach to the former Confederacy “left most abolitionists with no choice but to support Grant,” even if they were dissatisfied with him (McPherson, 1965, p. 44).

Despite the alliance opposing him, Cambridge gave Grant a bigger victory than he had in 1868. All five wards posted a Republican swing; the biggest (31%) came in Ward 5. Greeley largely failed to inspire Democratic voters to come out for him; statewide, around 30% of Seymour’s voters in 1868 sat out 1872 (Baum, 1984, p. 176).

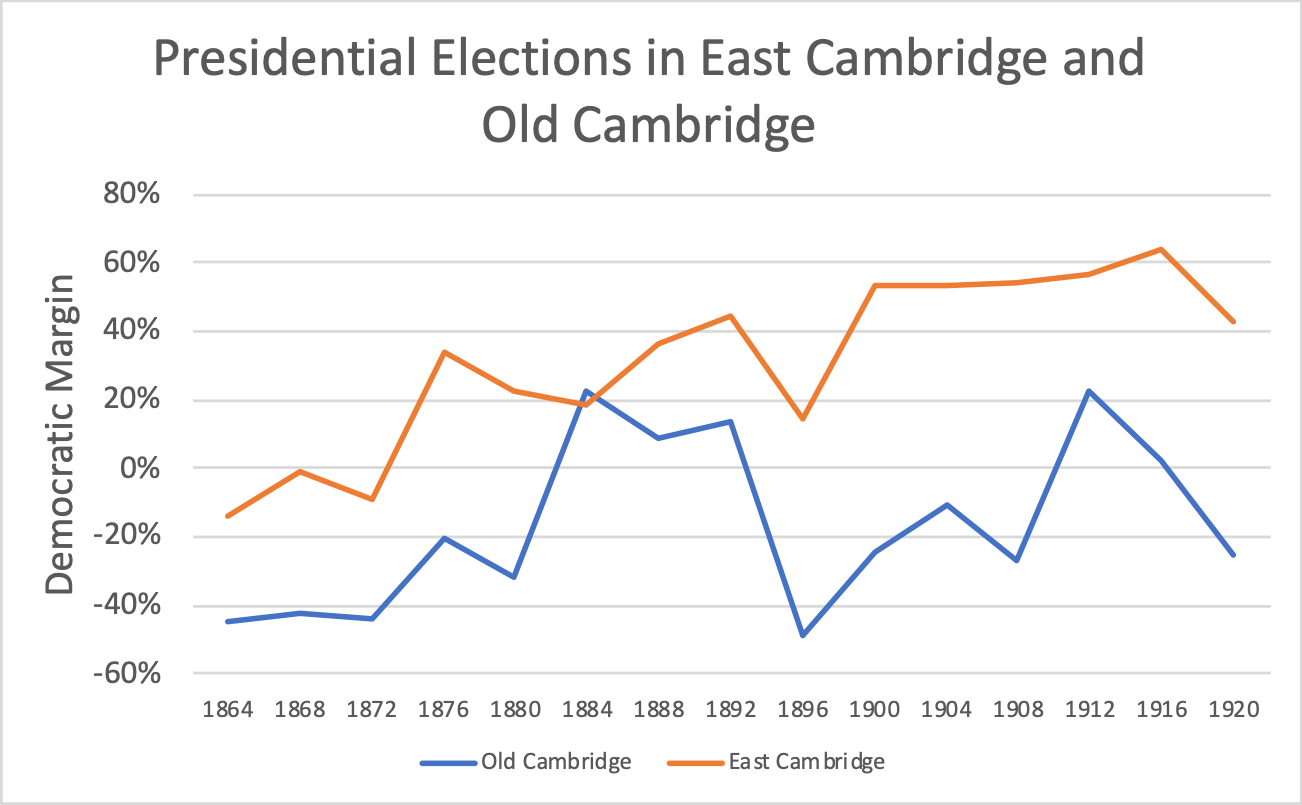

This was the last time any ward encompassing East Cambridge voted Republican for President. As such, it was the last time that a Republican carried all of Cambridge’s wards. Massachusetts’ Irish-born voters were somewhat divided in 1868 and 1872; around one-third of them went for Grant on both occasions (177). The consolidation of the Irish vote along with continued immigration from elsewhere in Europe solidified East Cambridge as a Democratic stronghold, much like other industrial urban cores of the era.

1876

In 1873, Benjamin Butler, a mercurial politician widely viewed as corrupt, ran for the Republican gubernatorial nomination. He lost, but President Grant later appointed his campaign manager to oversee the Boston Custom House. Grant’s term was heavily defined by nepotism, and this brazen act of patronage hit close to home, prompting “talk of a party revolt against Grant” among Massachusetts Republicans (Baum, 1984, p. 188). An economic depression generated further discontent directed at the Republican Party. Consequently, the 1874 elections saw Democrats flip the state legislature and pick up the governorship for the first time in 22 years.

Around this time, some Republicans wanted to break from the national party and organize an independent reformist movement to “hold the balance of power between the Grant faction of the Republican party and the southern Democrats” (200). Those hopes were quashed, however, amid a political environment characterized by profound apathy (200). The 1876 Republican convention nominated Rutherford B. Hayes — a safe, inoffensive choice which “generated little enthusiasm” among the reform-minded Republicans (205).

As the presidential campaign began, the Chronicle opined that Hayes’ association with Grant would drag him down. “The Republican party has, in one respect, a fearfully heavy load to carry,” a July editorial warned. The paper’s disdain for the President’s administration was palpable: “[Grant] has opposed every honest cabinet officer,” it fumed, “and supported with zeal the thieves and plunderers who have robbed the treasury” (Jul. 15, 1876). Yet the rock-ribbed Republican editors could not bring themselves to support Democrat Samuel Tilden. “Governor Tilden may be the most honest of men, personally,” they admitted, but “the folly of electing a candidate on personal grounds has been often demonstrated.”

Cambridge Democrats were highly enthusiastic and started campaigning early. Upon witnessing their kickoff event, the Chronicle cautioned that “every effort possible will undoubtedly be made to cast the highest Democratic vote this fall, ever known in Cambridge” (Aug. 12, 1876). As anticipated, the Democrats’ main strategy consisted of relentlessly tying Hayes to Grant. At one rally in Old Cambridge, a speaker argued that “the election of Mr. Hayes will be but a continuation of the corruption of President Grant” (Chronicle, Sep. 16, 1876).

Ultimately, Hayes squeaked out a narrow win. At the time, this was by far the closest presidential race in Cambridge’s history. All five wards swung sharply toward the Democrats, as Tilden came within single digits of carrying Ward 2 and nearly cracked 40% in Ward 1. The Democrats’ coalition in Massachusetts combined disaffected Republicans and first-time voters; statewide, approximately 50% of Tilden voters had not chosen Seymour in 1868 (Baum, 1984, p. 209). Tilden’s decisive victory in East Cambridge marked an inflection point in that area’s political alignment; never again would it be competitive for Republicans in a presidential election.

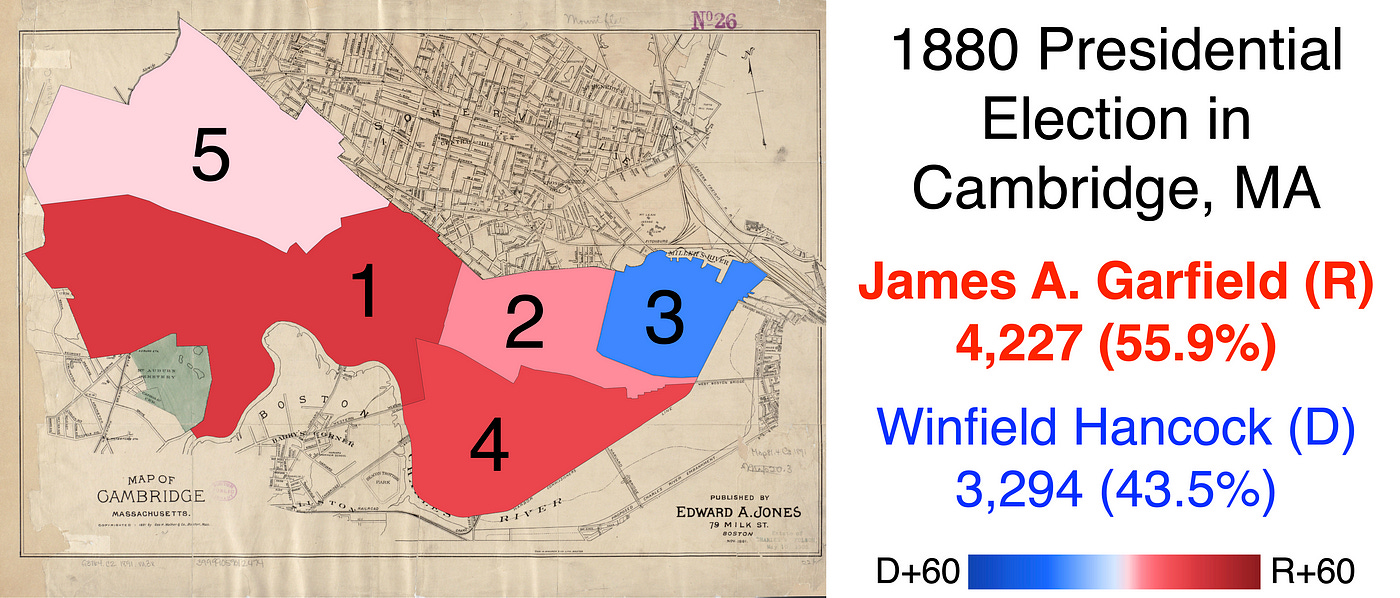

1880

Republicans began the 1880 campaign reprising their familiar theme of “waving the bloody shirt” — reminding voters that Democrats were traitorous rebels during the Civil War — despite the fact that Democratic nominee Winfield Hancock served in the Union Army (Clancy, 1958, p. 175). “The great question,” a Cambridgeport Chronicle reader wrote in a letter, “is this: shall we permit our government to pass completely into the hands of Rebel leaders” (Oct. 9, 1880).

Tariffs were another major point of contention in the campaign. The Democratic platform included vague language on the issue, stating that the party supported “a tariff for revenue only” — that is, it did not support protective tariffs meant to benefit domestic producers. This position alienated blue-collar laborers, particularly in the North. The Chronicle asserted in October that the tariff issue “is so great as to completely override all others” (Oct. 23, 1880). “If the policy of a tariff for revenue only prevails,” it warned, “the millions of dollars invested in Lowell, Fall River, New Bedford … will be worth about fifty cents on the dollar.”

After Hayes’ close shave, the paper’s editors confidently predicted that many Republicans would fall back in line for 1880 (Chronicle, Aug. 7, 1880). While Republican James A. Garfield’s victory was far from overwhelming, it was indeed more comfortable than Hayes’. Perhaps owing to the Democratic position on tariffs, Garfield made up ground in East Cambridge. The Chronicle noted that Hancock was expected to carry the ward by 500 to 600 votes, but ended up winning by just 323 (Nov. 6, 1880). Less surprisingly, the Republican strongholds of Wards 1 and 4 saw double-digit swings away from Democrats with the unpopular Grant out of the picture.

At the time, Wards 2 and 4 comprised an open-seat state house district. Even though observers expected Garfield to carry the district, Republican nominee George Chamberlain was considered vulnerable. “Mr. Chamberlain will naturally run considerably behind his ticket,” the Chronicle correctly forecasted in October (Oct. 23, 1880). A city alderman, Chamberlain held extreme views on Prohibition and a singular obsession with the issue (Chronicle, Nov. 6, 1880). Chamberlain ran 14 points behind Garfield but managed to prevail, 53–47.

For the 1848–1924 time period, this was the election where Cambridge and Boston diverged the most; Cambridge voted 16 points more Republican than Boston.

1884

The 1884 campaign brought a major shakeup to the Republican Party. The national convention selected James G. Blaine, a Senator with a reputation for scandal. One incident stood out: while he was Speaker of the House, Blaine accepted bribes from railroad companies. Letters substantiating the charges were widely circulated (Winick, 2016). A group of Republican activists, united by their steadfast opposition to corruption, decided to abandon their nominee. These voters, known as Mugwumps, were especially prevalent in Massachusetts. Indeed, “conscience-soaked Boston was undoubtedly the Mugwumps’ nest” (Wood, 1960, p. 435). Such figures as widely revered President of Harvard Charles W. Eliot and prominent editor Charles Francis Adams declared their support for Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland; three traditionally Republican newspapers in Boston endorsed him (Muzzey, 1934, p. 295). Yet although the most high-profile Mugwumps in Massachusetts were established intellectuals, the movement also attracted many young Republicans already upset with the state party. Old-guard politicians dominated the upper ranks of the party’s hierarchy, fomenting discord among aspiring leaders clamoring for mobility. Edward Everett’s son, William, complained that “the old men of the party are doing their best to snub the young men of the party who would like to belong to it” (Wood, 1960, p. 436).

Massachusetts Democrats, meanwhile, had their own schism to ponder. Their growing Irish-American contingent increasingly felt that the “old Yankee element” of the party was taking them for granted (438). Benjamin Butler, running as a Democrat, exploited their anger to win the governorship in 1882 to the Brahmins’ chagrin (438). In 1884, he contested the Democratic presidential nomination, denouncing Cleveland as a “respectable” (439). Cleveland, a reformer who loathed the political machines Butler so deftly leveraged, was “the type of politician Butler abhorred” (Trefousse, 1956, p. 187). At the convention, Butler tried determinedly to influence the platform, but his entreaties were repeatedly rejected (188). When it became clear that Cleveland would be selected as the nominee, Massachusetts’ Irish party leaders turned apprehensive. They dreaded the concept of voting for the Mugwumps’ candidate and were suspicious that Cleveland would not stand firmly behind Catholics and laborers (Wood, 1960, pp. 439–440). The editor of the Democratic-leaning Boston Pilot reacted with alarm, writing that Cleveland’s nomination was “Democratic suicide” (Chronicle, Aug. 2, 1884). A furious Butler launched an independent campaign for president; local outlets took his campaign seriously, believing his presence on the ballot would cause substantial Democratic defections. In September, the Chronicle remarked that Butler’s movement “seems to be a strong one” (Sep. 27, 1884).

Yet heading into the campaign’s home stretch, Cambridge Republicans were not inspiring confidence. When the calendar turned to October, the Republican city committee had still failed to organize a ratification meeting for Blaine’s candidacy — something that their counterparts in “every other city and town in the State” had already attended to (Chronicle, Oct. 4, 1884). Two weeks before the election, the committee was running short on funds. “What Have They Done With The Money?” asked a Chronicle headline on October 25. “All admit that some of the wealthy members of the party have gone over to the mugwumps,” the story contended, “but for all that there should be money enough.” Reflecting the intraparty divisions among the Republicans, the editors produced a rather tepid endorsement of Blaine: “while we are not of those who believe that any election will result in ruining the country,” they wrote, “it is yet our firm conviction that her best interests demand a continuation of Republican rule” (Chronicle, Nov. 1, 1884).

The Mugwumps’ impact was as advertised. Cleveland won the city and the election, becoming the first Democrat ever to carry Cambridge. Remarkably, his strongest performance came in Ward 1, where he defeated Blaine 58–35. This was a whopping 55-point Democratic swing from 1880; up to this point, Old Cambridge had reliably been Democrats’ worst neighborhood in presidential races. The Chronicle, comparing the performances of Blaine and downballot Republicans, concluded that “about 475 Cambridge Republicans bolted Mr. Blaine” (Nov. 8, 1884). Cleveland narrowly carried Ward 2, also a first for a Democrat. Butler’s impact, on the other hand, was far smaller than anticipated: he did split the Democratic vote in East Cambridge, collecting 14% in Ward 3, but that was nowhere near enough to jeopardize Cleveland’s win. The Chronicle predicted that Butler would receive 1,200 votes citywide—he managed just 664 (Oct. 11, 1884).

Thanks to the combined effects of Butler and the Mugwumps, this was the only time between 1848 and 1924 that a ward containing Old Cambridge voted more Democratic than a ward containing East Cambridge.

1888

Tariffs were back in the spotlight this election. President Cleveland advocated for tariff reform in his 1887 address to Congress, and the issue remained salient heading into 1888. Previewing the summer campaign, the Chronicle remarked that “the tariff question is all there is of either platform” (Jun. 30, 1888). It described Benjamin Harrison, the Republican nominee, as “a thoroughly respectable average man, eminently lacking in magnetic power and scarcely known.” Thus, the Mugwumps planning to vote Democratic again were more likely to be motivated by policy disagreements than personal grudges. Some Mugwumps had, for the time being, embedded themselves in the state Democratic Party apparatus; although Irish leaders still resented their presence, they were reluctantly accepted since the party was short on funds and needed all the support it could get (Wood, 1964, p. 445).

The relative dearth of inflamed discourse produced a forgettable campaign. Four weeks before election day, the Chronicle marveled: “it is positively astonishing how little real enthusiasm or interest is being exhibited in the election this year” (Oct. 13, 1888). The editors noted that the Mugwumps were not exhibiting the level of unity they displayed in 1884: “as to the Independents who form so important a body in Old Cambridge, they appear to be all at sea this year and are becoming pretty well divided among themselves.”

The paper, normally awash with dramatic exhortations venerating the year’s Republican candidate, seemed decidedly indifferent to Cleveland’s presidency. “The fact is,” it admitted, “there is really very little difference between the two great parties now” (Chronicle, Oct. 13, 1888). The editors declined to issue a formal endorsement, even expressing soft support for Cleveland in an election-week editorial. They reasoned that tariff reform far eclipsed every other issue in importance, and that the Democrats’ support for reform was genuine whereas the Republicans’ was acquiescent. The piece concluded matter-of-factly: “we incline to the belief that it will, on the whole, be better for the country for Mr. Cleveland to be re-elected” (Chronicle, Nov. 3, 1888).

Cleveland emerged victorious in Cambridge for a second time. His margin was slightly reduced, but the decreased third-party vote enabled him to win a majority. Although Ward 1 swung 14 points toward the Republicans, it remained more Democratic than the city for a second consecutive election. Absent Benjamin Butler’s presence, Cleveland romped to a 68–32 victory in Ward 3. Despite the lackluster campaign, turnout was extremely strong, with nearly 90% of eligible voters casting a ballot (Chronicle, Nov. 10, 1888).

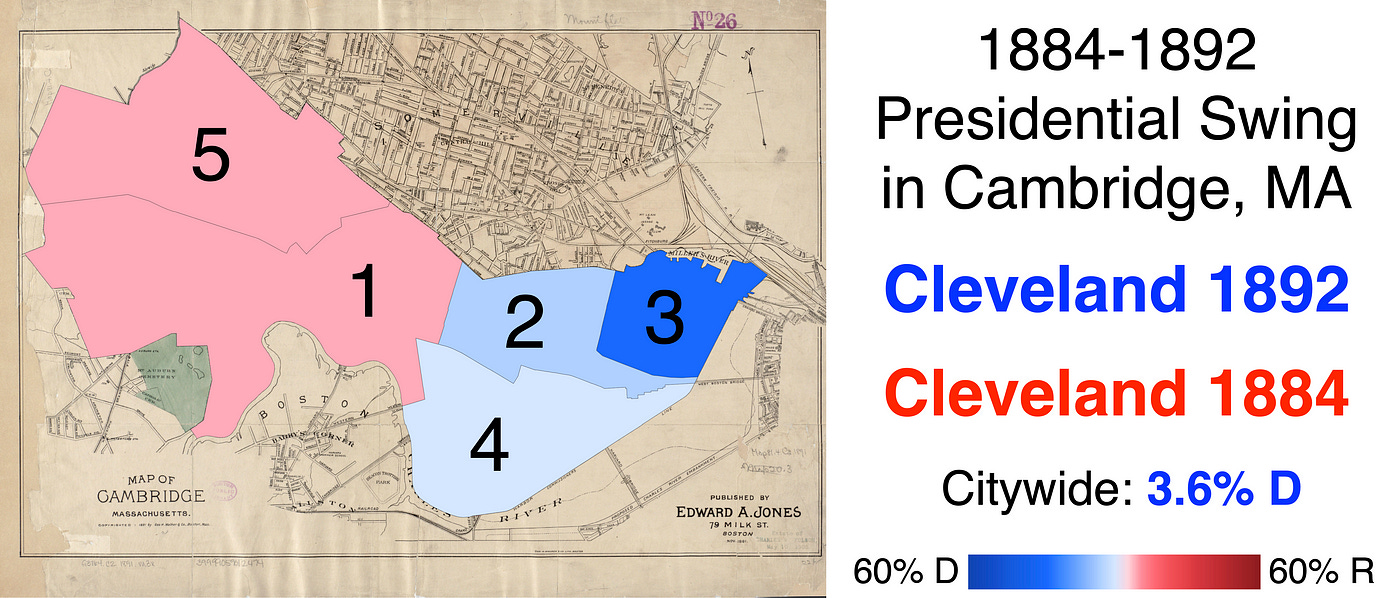

1892

The 1892 election featured a rematch between Cleveland and Harrison. The presence of two known quantities set the stage for another rather sleepy race. The Cambridge Tribune stated that both candidates were “honest and safe” so “personal questions are therefore largely eliminated from this election” (Aug. 6, 1892). In September, the Tribune described “a singular and unprecedented apathy” characterizing the campaign (Sep. 17, 1892).

Tariffs reprised their role as the centerpiece of the campaign (Knoles, 1942, p. 168). At the Democratic convention, Cleveland touched on just two policy issues in his acceptance speech: tariffs and election security (145). The Democrats favored reducing tariffs, whereas the Republicans defended the large McKinley Tariff passed under President Harrison. William McKinley, the bill’s namesake, embarked on a speaking trip; his speeches, imbued with nationalistic appeals, “defended [the tariff] as the bulwark of American manufacturers and workingmen against foreigners” (168).

Harrison’s image among Irish Catholics was tainted by his management of Native American boarding schools. The Catholic Church frequently won contracts to place missionaries and teachers in these schools (Knoles, 1942, p. 217). Harrison’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Thomas J. Morgan, was zealously anti-Catholic. He ordered “an inspection tour of the federal schools” which resulted in “an almost clean sweep of every Catholic teacher” (Sievers, 1952, p. 143). Across the country, Catholic media outlets were furious. One Catholic newspaper editor personally advised Cleveland that “the bigotry of the Republican Party could be and should be made the issue” in New England and the Northeast (155).

The New England state elections that occurred before November boded poorly for Harrison’s chances on election day (Knoles, 1942, p. 204). Indeed, Cleveland scored a third consecutive victory in Cambridge, this one larger than the previous two. He had his career-best showing in Ward 4, only losing it 49–47; this configuration of the ward never voted Democratic before boundaries changed, and Cleveland’s showing here was as close as it came. Interestingly, Ward 5 flipped from Cleveland to Harrison. However, its small size meant Cleveland’s gains elsewhere — like in Ward 3, where he broke 70% of the vote — mattered more.

Third parties fared poorly in Cambridge this cycle. The anti-monopoly Populist Party emerged on the national stage this election, taking 8.5% of the national vote. However, its primary appeal was to agrarian communities in the Mountain West, and in New England “the movement was generally ignored” (199). Their nominee, James B. Weaver, won a paltry 0.5% of the Cambridge vote. Additionally, a slate of Prohibition Party candidates largely underperformed expectations in local races; in one race for State Senate, the Chronicle concluded that for the Prohibitionists, “this result, after all the fuss and feathers made … must be scathing and indeed humiliating” (Nov. 12, 1892).

1896

An economic depression struck in 1893, helping “free silver” to become a salient issue in American politics. At the time, the U.S. was on the gold standard. Free silver meant that people who owned silver bullion would be allowed to convert it into coins; those coins would then be legal tender. This idea primarily appealed to Western farmers, many of whom were deeply indebted and stood to benefit from the inflation it would trigger.

William Jennings Bryan was a talented orator and passionate advocate for silver. Relatively unknown before the Democratic convention, he captured the nomination after taking the delegates by storm with his famous “Cross of Gold” speech. Since President Cleveland was a staunch defender of the gold standard, the platform adopted at the convention explicitly repudiated his administration (McSeveney, 1972, p. 165). For Northeastern Democrats, Bryan’s nomination would prove a stark test of party loyalty since “precious few sympathized with the agrarian-silverite coalition that now dominated the national Democratic party” (166).

In the wake of the convention, “scores of urban newspapers that had backed every Democratic candidate for a generation” promptly disavowed Bryan (Kazin, 2007, p. 61). The Chronicle described the dilemma that Massachusetts Democrats faced: the national and state platforms now differed so much that participation in national party activities would cause them to “be excluded … as much as if they participated in Republican caucuses” (Aug. 1, 1896). The staunchly Democratic Boston Post featured the reactions of prominent Bostonians, a vast majority of whom pledged to vote against Bryan. Albert Bosson, the former Democratic mayor of nearby Chelsea, proclaimed: “I shall never vote for a silver man as long as I live” (Jul. 11, 1896). Another man reckoned: “I hate to vote for McKinley, but will do so … McKinley stands for everything I do not believe in, except free silver.”

Although he was a dyed-in-the-wool populist, Bryan struggled to win over urban factory workers, whose circumstances bore little similarity to those of the Mountain West farmers who venerated him. Laborers “had nothing concrete to gain from free silver and would only suffer if a change in the currency drove up prices for food and other necessities” (Kazin, 2007, p. 69). On the campaign trail, McKinley warned voters that a Bryan win would lead to shuttered businesses and waves of layoffs (70).

Furthermore, Bryan’s anti-establishment rhetoric deeply alienated those who identified with the nation’s elite (65). Naturally, the blue-blooded Republicans of Cambridge were offended. The Chronicle sneered that Bryan “seems to have a hatred of everybody who has prospered” and that “his mission, as he sees it, is to tear down and destroy — to undo the work of all that have preceded him” (Sep. 26, 1896). It is perhaps unsurprising that Harvard’s student body was nearly unanimous in their support for McKinley; as the Tribune quipped, “it would take Diogenes more than one lamp to find a free silver man among the 3600 youths who are enrolled in the catalogue of the University” (Oct. 17, 1896).

McKinley routed Bryan in Cambridge, 65% to 29%. The intellectual bastion of Ward 1 swung an astounding 62 points toward the Republicans. 12% of the vote there went to John Palmer, a gold-supporting Democrat who ran in protest of Bryan and performed best in the Northeast (McSeveney, 1972, p. 190). Bryan turned in the worst Democratic showing in Ward 3 since 1872, yet he still carried it by 15 points; that made it a then-record 51 points more Democratic than the city. In Ward 4, which became Cambridge’s most Republican ward after the Mugwump revolt, McKinley clobbered Bryan 77% to 18%—to date, the biggest Republican win in any ward at any point in Cambridge’s history. Despite Cambridge’s population increasing by nearly 30,000 between 1880 and 1896, Bryan managed to win fewer raw votes than Winfield Hancock in 1880.

As Massachusetts went for McKinley quite uniformly, this was the election in the 1856–1924 period where Cambridge’s margin was closest to the state’s. In fact, most of America’s cities were more strongly Republican than its rural areas this election. The New England countryside was unique, though: it was dominated by conservative landowners — who held little sympathy for Bryan — rather than farmers (Diamond, 1941, p. 304).

To date, this is the largest Republican victory in Cambridge’s history.

1900

While Bryan was renominated without serious opposition, his second national campaign struck a decidedly different tone. The economy was humming again, so free silver was no longer the galvanizing issue it was four years prior. Thus, it took a back seat on the campaign trail, where he “seldom mentioned silver, unless a reporter asked him about it” (Kazin, 2007, p. 106). Instead, Democratic attacks focused on President McKinley’s support of imperialism.

When the Spanish-American war began, Bryan was sympathetic to the Cuban cause, believing that the Cubans were suffering and the U.S. had a moral imperative to win their freedom (86–87). However, when McKinley and the Republicans turned their focus to annexing and “Christianizing” the Philippines, Bryan took issue. He believed that by engaging in colonization, McKinley was ceding the moral high ground he gained from freeing the Cubans (89). Anti-imperialism thus became the principal cause of his campaign (100).

At the time, New England was “the bastion of the anti-imperialist movement” (108); the foremost anti-war organization was the Boston-based Anti-Imperialist League. Founded by former Massachusetts Republican Gov. George Boutwell, the League held many of its rallies at Faneuil Hall (Zack, n.d.). Boutwell proclaimed that he supported Bryan to “save the country from its most dangerous foe — imperialism” (Boston Post, Sep. 7, 1900). The League’s leaders, “mugwumps over the age of sixty,” were somewhat reluctant Bryan supporters; they still harbored a distrust of him despite their opposition to war (Kazin, 2007, pp. 91–92). Some Cambridge Republicans remained skeptical of Bryan’s purported concern for Filipinos, since national Democrats were simultaneously endorsing segregation in the Deep South. “What, then, except imperialism,” the Chronicle asked, “is the disenfranchisement of the negroes in violation of the Constitution?” (Sep. 29, 1900)

Although McKinley won a more comfortable victory nationally, his margin fell sharply in Cambridge. The Chronicle and Tribune both attributed the swing to anti-imperialist sentiment. Wards 1 and 4 each became around 25 points more Democratic. With the silver issue much diminished in importance, Bryan reached three-quarters of the vote in Ward 3, the highest for a Democrat yet. Differential turnout also appeared to benefit him: Ward 4 saw an 11% drop in votes cast while Ward 3 posted a 5% increase.

In the 1860s, Ward 2 was as deeply Republican as Ward 4. After that, however, Ward 2 steadily became more Democratic; the two wards diverged more than ever in the 1900 race, as Ward 2 was 38 percentage points more Democratic than Ward 4. One possible explanation for this divergence is Ward 2‘s closer proximity to the continued industrial development in East Cambridge. Along with supporting Bryan, the ward elected two Democrats to the state legislature this cycle. The Chronicle noted that “the ward is clearly Democratic, and increasingly so” (Nov. 10, 1900).

1904

Cambridge moved to an eleven-ward arrangement in 1901, leaving behind “its historic but outgrown five” (Chronicle, May 25, 1901). The law required state legislative districts to stay intact, which is why Ward 2 was split in three while every other ward was split in two.

Here’s how the old wards mapped onto the new ones:

Ward 1 — split into Wards 8 and 9

Ward 2 — split into Wards 3, 4, and 5

Ward 3 — split into Wards 1 and 2

Ward 4 — split into Wards 6 and 7

Ward 5 — split into Wards 10 and 11

In 1904, Democrats did an about-face, temporarily abandoning Bryan’s populist crusades. Business-friendly “Bourbon Democrats” regained control of the party and nominated Alton B. Parker, Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals. Bryan openly criticized Parker, a conservative who supported the gold standard and was backed by corporate leaders (Kennedy, n.d.-a, p. 2). Theodore Roosevelt, who became President upon McKinley’s assassination and won the Republican nomination to run for a full term, was a progressive well-known for his trustbusting efforts. Indeed, Parker “was closer to wealthy businessmen … than Roosevelt was” (3).

The local papers’ reactions illustrate how muddled ideology and partisanship were this election. The Tribune praised Parker, describing him as hailing from “the solid and conservative element in the party” (Jul. 16, 1904). It rejoiced that “after eight years of flying off on the free silver tangent … the contest will be waged, next fall, on natural and normal issues.” In defense of the Republican ticket, meanwhile, the Chronicle used rhetoric not dissimilar to the last eight years’ worth of Bryan campaign material, writing that Parker was chosen “at the dictation of Wall street” (Jul. 16, 1904). “Roosevelt is the people’s candidate,” it contended, while “Parker represents the capitalists.” A Democratic-leaning newspaper in Boston endorsed Roosevelt with a telling headline: “Theodore Roosevelt, Democrat” (Tribune, Sep. 3, 1904).

Perhaps owing to the candidates’ similarities, Roosevelt ran somewhat weakly in the Republican-leaning parts of Cambridge. In the wards outside of East Cambridge, he won by seven points where McKinley had won by 14. These modest margins, combined with Parker matching Bryan’s performance in East Cambridge, enabled the Democrat to eke out a win.

Despite Parker’s showing in Cambridge, he was soundly defeated statewide; in fact, Cambridge and Boston were the only cities in Massachusetts to vote Democratic (Chronicle, Nov. 7, 1908). This election marked the first time that Cambridge voted 20 points more Democratic than the state. It was also the first time that a Democrat carried Cambridge without winning an Old Cambridge ward.

To date, this is the closest presidential election in Cambridge’s history.

1908

After Parker’s resounding nationwide defeat in 1904, Bryan retook control of the Democratic Party. He glided to the nomination, running on a platform reprising many of the populist policies he championed in 1896 and 1900. The platform included planks on restricting campaign contributions and mandating eight-hour workdays (Kennedy, n.d.-b., p. 2). Campaigning “explicitly as the champion of the American labor movement,” his consistent advocacy for labor unions spurred the American Federation of Labor to endorse a presidential candidate for the first time in its history (Kazin, 2007, pp. 155–156). “The Trusts,” the pro-Democratic Cambridge Sentinel charged, “is the great issue in the coming campaign” (Jul. 4, 1908).

Roosevelt’s handpicked successor, William Howard Taft, hardly possessed Bryan’s campaign skills: he “read out most of his speeches and said nothing worth remembering” (Kazin, 2007, p. 160). Yet he navigated the election cycle without major scandals or gaffes, presenting a competent mien (Kennedy, n.d.-b, p. 3). In turn, Cambridge Republicans viewed Taft as a steady hand whose triumph would avert the elevation of an opportunistic, unpredictable radical. Bryan “is an agitator by nature and by practice,” the Chronicle wrote (Aug. 29, 1908). The Tribune mockingly praised the “fertility of his imagination in supplying … issues based wholly on their securing political expediency” (Jul. 18, 1908).

Taft flipped Cambridge back into the Republican column, scoring a 52–43 victory. This earned Bryan an ignominious distinction: he remains the only Democrat ever to lose Cambridge on three occasions. Taft broadly improved over Roosevelt throughout the city; his gains were largest in Wards 8 and 9, the most closely connected to Old Cambridge and Harvard. “Capital,” the Chronicle remarked, was “timid and unwilling to take the chances” of a Bryan win (Nov. 7, 1908). In recapping the results, it described “a revolt among the college element against Bryan” (Nov. 7, 1908).

For the 1848–1924 time period, this was the election where East Cambridge voted furthest from the city as a whole. Bryan crushed Taft 75–21 there, making it 63 percentage points more Democratic than the city.

1912

For the initial portion of his term, President Taft maintained amicable relations with Roosevelt. However, the two men steadily drifted apart, and Roosevelt challenged Taft for the 1912 Republican nomination. Progressives in the Republican Party succeeded in holding first-of-their-kind presidential preference primaries. Not all states held primaries, but Roosevelt handily won in those that did (Chace, 2004, p. 113). Unfortunately for him, the Republican National Committee’s machinery was firmly aligned with Taft; in a blatant act of favoritism, it overwhelmingly awarded the non-primary delegates to him (116). Roosevelt made up his mind: the convention was a sham, and he would form his own Progressive Party to contest the general election (120).

Cambridge Republicans seemed to sympathize with Roosevelt voters, if not with Roosevelt himself. The Chronicle expressed skepticism that the Progressive Party’s formation was warranted, writing that it “cannot hope to thrive” on “the ephemeral issue” of the stolen convention (Jul. 6, 1912). It asked: “What fundamental principle is there for which the Progressives contend and which is not advocated either by Republicans or Democrats, and in some instance by both?” At a Republican city committee gathering in July, attendees welcomed party members planning to vote Roosevelt; the meeting decided that “their standing as loyal Republicans is not to be impugned” (Chronicle, Jul. 27, 1912).

Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson came to Boston in September, where “Brahmins joined with the Democratic Irish … to give him an overwhelming reception” (Chace, 2004, p. 216). There, he ran into Taft, and the two candidates had a cordial exchange. The Chronicle praised Wilson, contrasting his class with Roosevelt’s vulgar attacks of Taft. Roosevelt “may well learn from Governor Wilson that it is possible to be a party candidate for president and remain a gentleman,” the editors scolded (Sep. 28, 1912).

As the campaign progressed, it became clear Roosevelt’s support was almost exclusively drawn from Republicans. “The number of prominent Democrats in any way affiliated with the third party,” the Chronicle conceded, “may be counted on the fingers of one hand” (Aug. 3, 1912). John Fitzgerald, the Democratic mayor of Boston, was thrilled with the Progressives’ slate of local candidates, correctly anticipating that their siphoning of Republican votes would hand the state legislature to his party (Chronicle, Oct. 12, 1912). Naturally, Republicans fretted over the inevitable. One Cambridge Republican, justifying his support for Taft to a Progressive friend, asserted: “a vote for Roosevelt is clearly a vote for Wilson” (Chronicle, Oct. 26, 1912).

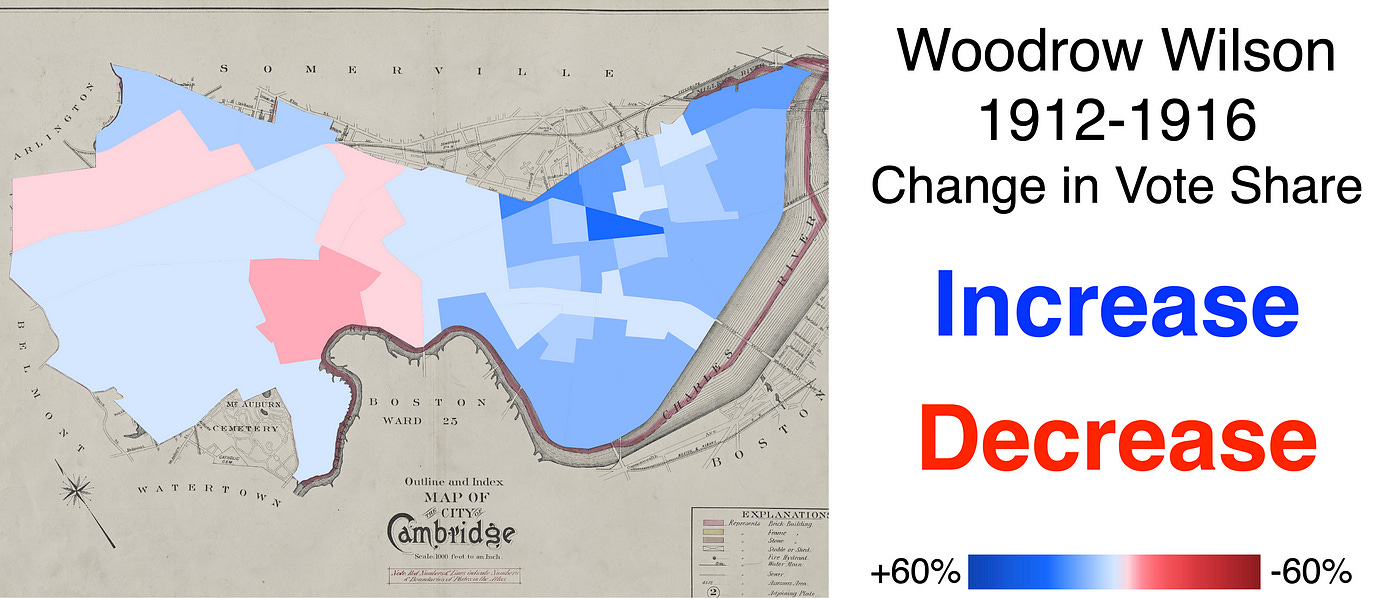

Despite winning a majority in only four wards, Wilson coasted to victory. Taft and Roosevelt were separated by just 50 votes. Republicans’ worst fears were realized: Democrats swept Cambridge’s state house seats for the first time in the city’s history (Chronicle, Nov. 9, 1912). Harry Stearns, a state senator whose district comprised Wards 5 through 11, was the lone surviving Republican. “Cambridge was hit harder by the Democratic landslide Tuesday than even the most ardent partisan had dared to predict,” the Chronicle admitted (Nov. 9, 1912).

Although Wilson’s win came primarily due to Republican division, he did appear to make inroads with some anti-Roosevelt Republicans. The Chronicle claimed that these voters opted for Wilson out of spite to ensure TR’s defeat (Nov. 9, 1912). Wilson garnered 46% of the vote in Ward 9, a 15-point improvement over Bryan’s 1908 showing. Meanwhile, Roosevelt managed to win a small minority of Democrats — Wilson earned 69% in East Cambridge, down from Bryan’s 75%.

By carrying Ward 6, Roosevelt became the first (and to date, only) third-party presidential candidate ever to win a Cambridge ward.

1916

President Wilson’s re-election campaign hammered home two themes: progressivism and peace. During his first term, Wilson championed several pieces of high-profile legislation addressing priorities Roosevelt advocated for in 1912. In accepting re-nomination, Wilson made his pitch to former Roosevelt voters clear. “We have in four years come very near to carrying out the platform of the Progressive party,” he proclaimed, “for we are also progressives” (Link, 1965, p. 94). This outreach dovetailed neatly with his message of peace, since progressives were overwhelmingly pacifists (108). World War I was raging in Europe, but the U.S. had yet to enter the fray. Wilson portrayed a vote for Republicans as a vote for war: “there is only one choice as against peace, and that is war” (106).

The Republicans nominated Charles Evans Hughes, a former Supreme Court Justice. Hughes won the nomination largely due to backing from business leaders upset with Wilson’s friendliness to organized labor. In particular, they were frustrated with the Adamson Act, which guaranteed an eight-hour workday for railroad workers (103). The balancing act Hughes tried to pull off in uniting the Republicans’ progressive and business-friendly wings left him unable to coherently articulate what he stood for (100). The Chronicle admitted that Hughes’ speeches often denounced Democratic rule rather than offering a constructive case for his election, but still supported him (Aug. 12, 1916).

Many Irish-American publications were initially sour on Wilson; after British authorities crushed an armed uprising from Irish nationalists and executed the rebels, he had declined to intervene (Leary, 1967, p. 61). However, excitement for Hughes among the Irish press was never great and “diminished considerably” as the campaign wore on (64). Indeed, “even the most vociferous of the Irish-American newspapers was unable to work up any enthusiasm for his candidacy” (71). In the most heavily Irish neighborhoods of Boston, Wilson would run ahead of both his 1912 showing and Bryan’s 1908 performance (68).

As Hughes failed to rally liberal Republicans, “independent progressives — social workers, sociologists, and intellectuals — moved en masse into the Wilson column” (Link, 1965, p. 124). Cambridge proved no exception to this trend: Charles W. Eliot, the popular former Harvard president, supported Wilson. He wrote that Hughes’ acceptance letter consisted solely of generic platitudes to which “nearly all American voters would subscribe” (Tribune, Oct. 7, 1916). Bliss Perry, a Harvard professor, criticized Hughes for failing to express a coherent foreign policy plan (Tribune, Oct. 21, 1916). Meanwhile, Cambridge Democrats happily claimed the mantle of progressivism. At a rally in nearby Somerville, a state senator declared Wilson to be “the second great emancipator of the country” for his efforts passing the Federal Child Labor Act (Tribune, Oct. 28, 1916).

Wilson won Cambridge for a second time, claiming the majority that eluded him in 1912. His vote share increased in all but one ward — ancestrally Republican Ward 9. In heavily Irish East Cambridge, he trounced Hughes 78–14, setting a new high-water mark for Democrats. Even the traditionally Republican parts of the city were competitive this election; Hughes was held to single-digit margins in Wards 7 and 9, and his biggest victory was a modest 54–42 win in Ward 10.

Even as Wilson carried the city by double digits, first-term Republican Rep. Frederick Dallinger won Cambridge 51–49 in his successful re-election bid, outrunning Hughes in all but one precinct.

1920

By the 1920 campaign, President Wilson’s reputation was damaged. He had reneged on his promise not to enter the war; the economy was sputtering. After the war, he negotiated the Treaty of Versailles, which called for the creation of a League of Nations. He failed to secure enough support from Senate Republicans to get it passed, stubbornly refusing to negotiate with them (Schmuhl, 2020). In a largely futile effort, Democrats again attempted to campaign on progressivism. Amid Wilson’s deep unpopularity and a tumultuous social environment characterized by riots and strikes, this messaging fell flat. Historian Wesley M. Bagby (1962) wrote that the campaign’s “most striking feature” was the ineffectiveness of progressive themes that resonated so strongly in 1912 and 1916 (p. 150). The Sentinel admitted that Cambridge’s Republicans were “beating their rivals” since “the Progressives have … dropped back into the ranks” (Jul. 31, 1920). Republican Warren G. Harding campaigned on his now-famous “return to normalcy” slogan, promising calmness and healing amid the tension. “Harding and Harmony will be a good watchword,” the Chronicle beamed upon his nomination (Jun. 19, 1920).

Irish-Americans were particularly angry with Wilson. Despite championing the principle of self-determination, the President declined to support Irish independence during peace negotiations (Schmuhl, 2020). The Sentinel conceded that “there is unquestionably deep bitterness felt against Mr. Wilson for failure even to suggest consideration of the Irish problem” (Aug. 14, 1920). Knowing he needed to retain the President’s base, Democratic nominee James M. Cox fully embraced Wilson’s ill-fated push for the League (Bagby, 1962, p. 127). The Chronicle charged Cox with hypocrisy, alleging that he “labored hard to win votes for the league and then tried to make Irish voters forget their enmity to it” (Oct. 30, 1920).

Harding cruised to a decisive victory in Cambridge. “The people were sick and tired of Wilson and his administration,” the Chronicle quipped, “and that’s all there was to it” (Nov. 6, 1920). Harding’s 19-point triumph marked the largest Republican victory since 1896. Cox was held to carrying only East Cambridge and its immediate vicinity; even there, he easily became the worst-performing Democrat of the century. He badly underperformed Wilson in every ward, but the Republican swing was most severe in Ward 3. There, Cox’s 53–36 win paled in comparison to Wilson’s 77–16 demolition of Hughes.

Harding won a substantially larger victory statewide than he did in Cambridge; his Cambridge margin was likely dampened by Republicans who favored the League of Nations. The Chronicle described these voters as pacifists who supported Cox because they believed the League represented America’s only hope for peace (Oct. 23, 1920). Many presidents of liberal arts colleges fell into this category (Bagby, 1962, p. 138), and it seems reasonable they were overrepresented in Cambridge. Assessing the results, the Chronicle claimed that pro-league Republicans were especially concentrated in Old Cambridge (Nov. 6, 1920).

To date, this is the most recent presidential election where the Republican candidate won a majority in Cambridge.

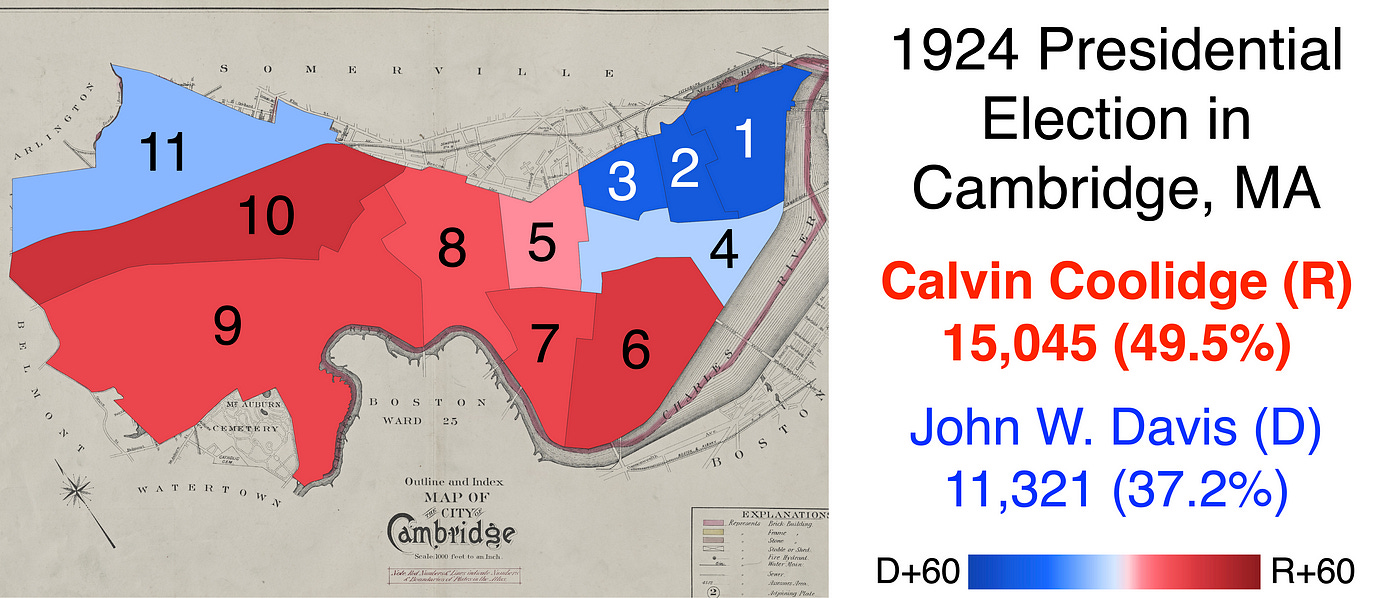

1924

After President Harding’s death in 1923, his Vice President — former Massachusetts Gov. Calvin Coolidge — took over the reins. The Democrats’ quest to select a challenger to Coolidge was severely hampered by intraparty division (Greenberg, n.d.). William G. McAdoo, a relative of former President Wilson, had strong support from rural Southerners and Prohibition advocates. Urban Northeasterners and anti-Prohibitionists, on the other hand, were deeply attached to New York Gov. Al Smith. The Sentinel reported that Cambridge’s delegation to the convention was “all rooting hard” for Smith (Jun. 7, 1924). In the end, the convention nominated neither candidate, choosing West Virginian John W. Davis as a compromise after a grueling 103-ballot contest (Greenberg, n.d.). Davis, a conservative lawyer, had policy positions very similar to Coolidge. The Chronicle complimented Davis, saying he “[stood] far above many of those who were mentioned for the nomination” (Jul. 12, 1924).

In a political climate defined by economic prosperity and broad-based optimism, Coolidge was widely popular (Greenberg, n.d.). Particularly in his native New England, he was viewed as a man of honesty and integrity; traditionally Democratic local papers freely admitted his character was unimpeachable. The Boston Post endorsed Coolidge “not because he is a Republican, but in spite of it” (Chronicle, Sep. 13, 1924). It praised him for “doing his duty competently and quietly,” declaring that “amid all the admitted wrongdoing of the Republican regime our New England president stands out clean and blameless.” Even the staunchly partisan Sentinel had to admit that “Coolidge has been a godsend to the Republicans, who are placing him upon a pedestal as custodian of all the public virtues” (Oct. 11, 1924). “It will not be easy,” the Chronicle presciently forecast, “to convince the voters of the country that the administration of President Coolidge is corrupt” (Sep. 27, 1924).

Progressives disenchanted by the major-party nominees’ conservatism flocked to Wisconsin Sen. Robert La Follette, who launched a third-party bid. La Follette ran doggedly on populist policies such as regulating monopolies and nationalizing railroads (Greenberg, n.d.). However, Republicans effectively rebutted his candidacy, portraying him as radical and framing the choice as “Coolidge or Chaos” (Shideler, 1950, p. 456). The Chronicle remarked: “There are a few voters who want chaos … the LaFollette following is largely of this type of voters” (Oct. 11, 1924). For his part, La Follette appeared to be running fairly well with Cambridge’s student population: in a Harvard straw poll, he garnered a solid 17% to Davis’ 26% and in a similar exercise at Radcliffe “LaFollette and Davis received almost equal numbers of votes” (Tribune, Nov. 8, 1924).

Coolidge won Cambridge by a sizeable 12-point margin. Thanks to La Follette’s presence in the contest, Davis matched Cox’s relatively weak performance in East Cambridge. The Sentinel attributed La Follette’s support to “the radical element among the local Democrats” (Nov. 8, 1924). The Chronicle suspected some Democrats still upset over Smith’s loss refused to vote for Davis (Nov. 8, 1924). Coolidge was strongest in Ward 10, where he reached 63% of the vote.

Even as Coolidge held on for one last Republican victory in Cambridge, the city voted a whopping 25 points more Democratic than the state — a record at the time. Democratic gubernatorial, senatorial, and congressional candidates all carried the city, making Coolidge’s win that much more impressive.

Charts

Epilogue

Al Smith ran for the Democratic nomination again in 1928; this time, he emerged victorious. Smith, a New York City-bred Democrat of Irish and Italian heritage, fit Cambridge like a glove. All across the country, immigrant-heavy urban areas turned out in droves for him, even as he went down in flames to Republican Herbert Hoover. Smith’s ardent Catholicism, a deal-breaker for masses of voters elsewhere, was an additional boon to his prospects in New England. He earned unprecedented margins in Cambridge’s working-class neighborhoods, taking an astonishing 93% of the vote in East Cambridge’s Ward 1. Four wards saw Democratic swings in excess of 50 percentage points. Smith became the first Democrat ever to earn 60% of the citywide vote; Hoover, the first Republican ever to drop below 40% in a two-party race.

Like many Northeastern cities, Cambridge never looked back. Over the next four elections, Franklin D. Roosevelt solidified Smith’s coalition for the Democrats; no wards flipped at all in either 1932 or 1936. After World War II, Cambridge briefly flirted with competitiveness again during Dwight D. Eisenhower’s two landslide victories. Eisenhower, who held broad appeal among moderate Yankee Republicans, managed to come within two points of winning the city in 1956.

Favorite son and Catholic John F. Kennedy was on the ballot in 1960; he won Cambridge in a blowout, 71–28. But it was the GOP’s Southern strategy, exemplified by Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign four years later, that precluded Republican competitiveness in Cambridge more permanently. Goldwater’s showing was far worse than that of any Republican preceding him, as he obtained a paltry 14% of the vote. The 1970s saw Cambridge become a nexus for countercultural sentiment; dozens of community organizations promoting feminist, environmentalist, and pacifist causes sprouted (Herwick, 2019). Thus, even as the unapologetically liberal George McGovern was getting destroyed nationally, he crushed Richard Nixon 74–25 in Cambridge. Ronald Reagan, in his two landslide victories, won 20 and 23 percent of the Cambridge vote.

George H.W. Bush in 1988 was the last Republican to exceed one-fifth of the vote in Cambridge. As the Republicans of the 1990s were increasingly catering to social conservatives, Cambridge was rapidly shedding its traditional image as a middle-class industrial city. Kendall Square, a neighborhood overlapping with East Cambridge, epitomized the city’s transformation. Starting with Biogen, which in 1983 moved its headquarters to an abandoned factory, a slew of nascent biotechnology and software companies purchased land in the Square (Blanding, 2015). Over the next few decades, the resulting economic boom turned the area into one of America’s most expensive commercial real estate markets; one firm’s $19 million investment in lab space turned into $13 billion (Spalding, 2018). Today, leading firms like Google and Pfizer employ thousands of workers in Kendall Square; sleek high-rises and novel restaurant concepts populate the neighborhood.

All this development led Cambridge to become even more cosmopolitan and college-educated than it already was. Accordingly, the Republicans’ vote share fell for five consecutive elections between 1992 and 2008. (Mitt Romney, for all his appeal to upscale New Englanders, produced a mere one-point GOP swing in 2012.) In an era of strengthening educational polarization, Democratic victories in Cambridge have gotten still more lopsided. Most recently, the city gave Joe Biden his largest margin of victory out of all 1,548 municipalities in New England: a 92% to 6% obliteration of Donald Trump. The Cambridge of today quite literally cannot be much bluer. Nearly a century after “Silent Cal” carried the city, his win will undoubtedly remain a historic achievement for many years to come.

References

Bagby, W. M. (1962). The Road to Normalcy: The Presidential Campaign and Election of 1920. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Baum, D. (1984). The Civil War Party System: The Case of Massachusetts, 1848–1876. University of North Carolina Press.

Blanding, M. (2015, August 18). The Past and Future of Kendall Square. MIT Technology Review. Retrieved December 26, 2021, from https://www.technologyreview.com/2015/08/18/10816/the-past-and-future-of-kendall-square/

Brown, T. (1983). Edward Everett and the Constitutional Union Party of 1860. Historical Journal of Massachusetts, 11(2), 69–81. https://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Brown-combined-1.pdf

Cambridge Historical Commission. (n.d.). Brief History of Cambridge, Mass. Retrieved December 25, 2021, from https://www.cambridgema.gov/historic/cambridgehistory

Cambridge Historical Commission. (1971). Survey of Architectural History in Cambridge: Cambridgeport (Vol. 3). The MIT Press.

Chace, J. (2004). 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft & Debs — The Election that Changed the Country. Simon & Schuster.

Clancy, H. J. (1958). The Presidential Election of 1880. Loyola University Press.

Cunningham, J. M. (2021, November 1). United States presidential election of 1864. Brittanica. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1864

Diamond, W. (1941). Urban and Rural Voting in 1896. The American Historical Review, 46(2), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.2307/1838945

Engle, S. D. (2017). “Under Full Sail”: John Andrew, Abraham Lincoln, and Standing by the Union. Massachusetts Historical Review, 19, 43–81. https://doi.org/10.5224/masshistrevi.19.2017.0043

Foner, E. (1970). Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. Oxford University Press.

Freeman, D. H. (2000, June). A Changing Bridge for Changing Times: The History of the West Boston Bridge, 1793–1907 (Thesis). Graduate Masters Theses. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses/1/

Fuess, C. M. (1930). Daniel Webster (Vol. 2). Little, Brown and Company.

Greenberg, D. (n.d.). The Campaign and Election of 1924. Miller Center. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://millercenter.org/president/coolidge/campaigns-and-elections

Hales, J. (June 1830). Plan of Cambridge made by John G. Hales, dated June 1830 [Map]. Retrieved from https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/25152g82x

Handlin, O. (1991). Boston’s Immigrants, 1790–1880: A Study in Acculturation. Harvard University Press.

Herwick III, E. B. (2019, September 4). When Cambridge Was A Counterculture Hotbed. GBH. Retrieved December 26, 2021, from https://www.wgbh.org/news/local-news/2019/09/04/when-cambridge-was-a-counterculture-hotbed

Hills, J. (1770) Boston Harbour, with the surroundings, &c. [177-?] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71000625/.

Kazin, M. (2007). A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Kennedy, R. C. (n.d.-a). 1904 Overview. The Presidential Elections: 1860–1912. Retrieved December 17, 2021, from https://elections.harpweek.com/1904/Overview-1904-2.asp

Kennedy, R. C. (n.d.-b). 1908 Overview. The Presidential Elections: 1860–1912. Retrieved December 17, 2021, from https://elections.harpweek.com/1908/Overview-1908-3.asp

Kierdorf, D. (2016, January 10). Getting to know the Know-Nothings. The Boston Globe. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2016/01/10/getting-know-know-nothings/yAojakXKkiauKCAzsf4WAL/story.html?outputType=amp

Knoles, G. H. (1942). The Presidential Campaign and Election of 1892. Stanford University Press.

Leary, W. M. (1967). Woodrow Wilson, Irish Americans, and the Election of 1916. The Journal of American History, 54(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/1900319

Link, A. S. (1965). Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace, 1916–1917. Princeton University Press.

Luthin, R. H. (1941). Abraham Lincoln and the Massachusetts Whigs in 1848. The New England Quarterly, 14(4), 619–632. https://doi.org/10.2307/360598

Maycock, S. E. & Cambridge Historical Commission. (1989). Survey of Architectural History in Cambridge: East Cambridge (Second Edition). Cambridge University Press.

McPherson, J. M. (1965). Grant or Greeley? The Abolitionist Dilemma in the Election of 1872. The American Historical Review, 71(1), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1863035

McSeveney, S. T. (1972). The Politics of Depression: Political Behavior in the Northeast, 1893–1896. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mulkern, J. R. (1990). The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts: The Rise and Fall of a People’s Movement. Northeastern University Press.

Muzzey, D. S. (1934). James G. Blaine: A Political Idol of Other Days. Dodd, Mead and Company.

Newman, L. (1944). Opposition to Lincoln in the Elections of 1864. Science & Society, 8(4), 305–327. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40399648

Rich, R. (1971). “A Wilderness of Whigs”: The Wealthy Men of Boston. Journal of Social History, 4(3), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/4.3.263

Rodley, E. (2017). “Three Distinct and Separate Communities.” History Cambridge. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://historycambridge.org/research/three-distinct-and-separate-communities/

Sacco, N. (2017, July 28). A FREE COUNTRY FOR WHITE MEN: THE LEGACY OF FRANK BLAIR JR. AND HIS STATUE IN ST. LOUIS. The Journal of the Civil War Era. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2017/07/free-country-white-men-legacy-frank-blair-jr-statue-st-louis/#_edn9

Schmuhl, R. (2020, June 21). American political culture, Ireland and the League of Nations. RTÉ.ie. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/american-political-culture-ireland-and-the-league-of-nations

Senate Historical Office. (n.d.). The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (1868) President of the United States. United States Senate. Retrieved December 11, 2021, from https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Impeachment_Johnson.htm

Shideler, J. H. (1950). The La Follette Progressive Party Campaign of 1924. The Wisconsin Magazine of History, 33(4), 444–457. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4632172

Sievers, H. J. (1952). The Catholic Indian School Issue and the Presidential Election of 1892. The Catholic Historical Review, 38(2), 129–155. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25015416

Spalding, R. (2018, October 5). How a Rundown Square Near Boston Birthed a Biotech Boom and Real Estate Empire. Bloomberg. Retrieved December 26, 2021, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-10-05/how-a-rundown-square-near-boston-birthed-a-biotech-boom-and-real-estate-empire

Sullivan, D. (2015, November 6). WAS NELLIE BARRY CAMBRIDGE’S FIRST IRISH HERO? Facebook. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://www.facebook.com/cambridgehistcomm/posts/today-we-have-a-story-about-nellie-barry-a-young-girl-from-north-cambridge-in-th/1715646198667185/

Trefousse, H. L. (1956). Ben Butler and the New York Election of 1884. New York History, 37(2), 185–196. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24470878

Winick, S. (2016, November 3). Election Week Special: “The Dodger” and the Election of 1884. Library of Congress. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2016/11/election-week-special-the-dodger-and-the-election-of-1884/

Wood, G. S. (1960). The Massachusetts Mugwumps. The New England Quarterly, 33(4), 435. https://doi.org/10.2307/362673

Zack, A. (n.d.). The American Anti-Imperialist League at Faneuil Hall. National Park Service. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/anti-imperialist-league-fh.htm